NASA testing nanosatellites to track global storms

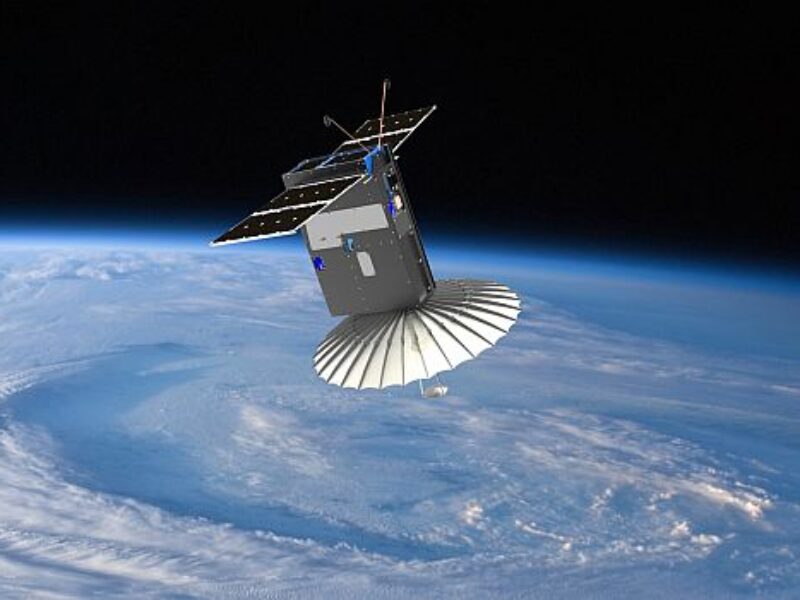

Deployed into low-Earth orbit from the International Space Station in July, the RainCube (Radar in a CubeSat), which is “no bigger than a shoebox,” is a technology-demonstration mission to enable Ka-band precipitation radar technologies on a low-cost, quick-turnaround platform. In an initial demonstration, the satellite sent back images of a storm over Mexico in August, and in a second wave of images in September it caught the first rainfall of Hurricane Florence.

The RainCube is a prototype for a possible fleet of such devices, say researchers, that could one day help monitor severe storms, lead to improving the accuracy of weather forecasts, and track climate change over time.

“We don’t have any way of measuring how water and air move in thunderstorms globally,” says Graeme Stephens, director of the Center of Climate Sciences at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “We just don’t have any information about that at all, yet it’s so essential for predicting severe weather and even how rains will change in a future climate.”

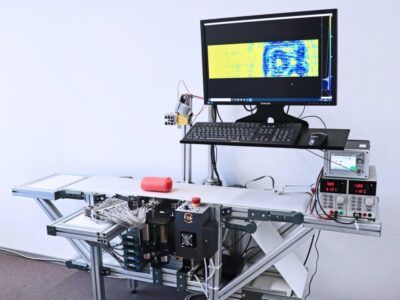

The researchers are experimenting to see if shrinking a weather radar into a low-cost, miniature satellite can still provide a real-time look inside storms. RainCube’s “umbrella-like” antenna sends out chirps – or specialized radar signals – that bounce off raindrops, bringing back a picture of what the inside of the storm looks like.

“The radar signal penetrates the storm, and then the radar receives back an echo,” says principal Investigator Eva Peral. “As the radar signal goes deeper into the layers of the storm and measures the rain at those layers, we get a snapshot of the activity inside the storm.”

RainCube is seen as a first demonstration that a mini-rain radar can work, but, say the researchers, it is not meant to fulfill a mission of tracking storms all by itself. Being miniaturized, it is less expensive to launch, and as a result, many more of such satellites could be sent into orbit and, flying together as a group, relay updated information on storms every few minutes – potentially yielding data to help evaluate and improve weather models that predict the movement of rain, snow, sleet, and hail.

“We actually will end up doing much more interesting insightful science with a constellation rather than with just one of them,” says Stephens. “What we’re learning in Earth sciences is that space and time coverage is more important than having a really expensive satellite instrument that just does one thing.”

“What RainCube offers on the one hand is a demonstration of measurements that we currently have in space today,” says Stephens. “But what it really demonstrates is the potential for an entirely new and different way of observing Earth with many small radars. That will open up a whole new vista in viewing the hydrological cycle of Earth.”

Related articles:

Satellite ultraviolet laser detector measures global winds

Miniature satellite propulsion system uses water vapor

Boeing invests in IoT nanosatellite communications startup

Iridium, AWS team on satellite IoT solution

If you enjoyed this article, you will like the following ones: don't miss them by subscribing to :

eeNews on Google News

If you enjoyed this article, you will like the following ones: don't miss them by subscribing to :

eeNews on Google News